AI-generated image created by Fakewhale.

The truth, old Roger liked to say, is that no one really understands contemporary art. “It’s already a miracle if the professionals understand anything at all…” he would sigh, lighting yet another cigarette behind the counter of his small gallery, which he had run for years in a remote corner of northern Washington State. A respectable place, of course, but still peripheral to the major art centers.

And it almost made us laugh, because he spoke as though there were actually something to understand. As though comprehension were a clear destination, a reachable end point. Yet the very idea of understanding, in contemporary art, is a slippery terrain: a semantic swamp where every step sinks into a new patch of quicksand. One does not advance through certainties here, but through approximations, attempts, hypotheses that last only as long as a gesture.

Roger knew this. Which is perhaps why he never spoke of “understanding” but of entering the work. He said that art is not something to be understood; it is something to be crossed, like a fog-drenched landscape where one glimpses more than one could ever grasp. The point is not to understand, but to accept that something will always escape us.

In fact, the lexicon of contemporary art creates a strange dynamic: while pretending to guide us toward comprehension, it often constructs a linguistic system that deliberately complicates the path. Criticism, curatorship, the institutional apparatus, even with the best intentions, amplify the distance between artwork and viewer, as if the artwork required a permanent preface in order to be truly seen.

And so, paradoxically, incomprehension becomes the very core of the aesthetic experience: not as a failure, but as a condition of possibility.

To understand a work of art does not mean to decode it, but to locate the field in which it challenges us. Every significant work introduces a fracture: a deviation from expectation, a slight disorientation that prevents the eye from closing itself into a comfortable conclusion.

Roger had his own way of putting it:

“If you understand a work immediately, it isn’t speaking to you. It’s only flattering you.”

This sentence, simple, almost naive, contains one of the most subtle truths of visual reading: art is not an exercise in translation, but a form of relation. And like any authentic relation, it is made of shadows, misunderstandings, and productive silences.

Unintelligibility is therefore not a problem to be solved, but a device to inhabit.

Its force lies precisely in its resistance to immediate meaning, in its ability to remain open, fluid, untamed by language.

In this new chapter through the labyrinth of art’s lexicon, we move not toward understanding, but toward the ways in which understanding fails and why that failure has always been the place where art begins to live.

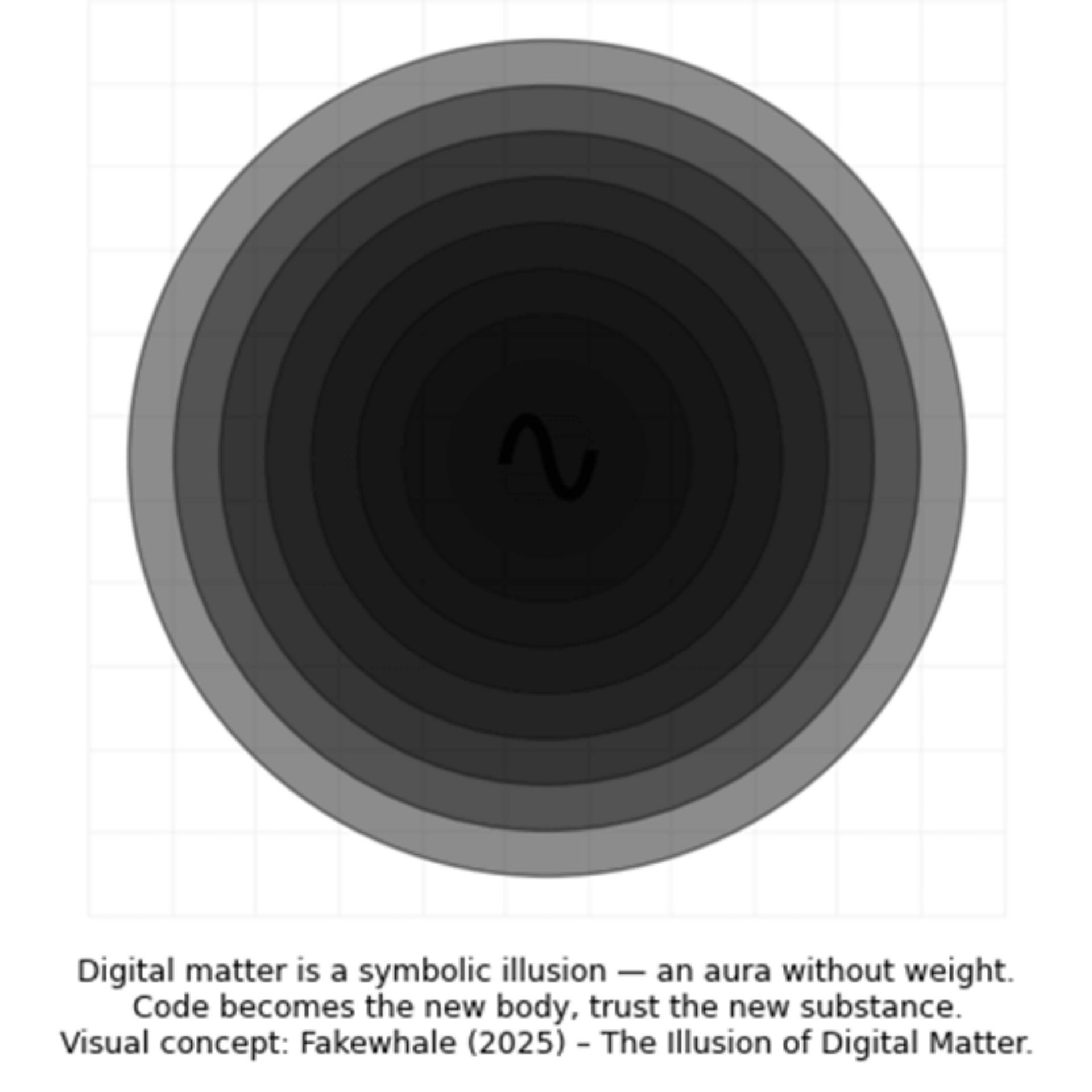

AI-generated image created by Fakewhale.

AI-generated image created by Fakewhale.

The Paradox of Understanding: Why Art Resists Clarity

The first major misunderstanding of contemporary art begins with the assumption that a work must be understood. It is a premise inherited from modernity, an era that expected every aesthetic object to come equipped with a code, a key, a clearly articulated communicative intention. Contemporary art breaks this structure apart: here clarity is not a goal but an occasional consequence, sometimes even an accident.

When we encounter a contemporary artwork, something happens that resembles walking into a room whose rules we do not yet know. We search for points of reference, we try to reconstruct an order, assign an orientation. And yet the work, especially if it is truly contemporary, is designed to elude exactly this attempt.

This is not elitism, nor an intellectual posture. It is an internal dynamic of the creative act.

Art does not affirm, it questions.

It does not clarify, it complicates.

It does not close, it opens.

And this is not because it aims to be unintelligible, but because it emerges from a matrix that is not yet meaning: perception, intuition, conflict, residue, gesture. Clarity is a linguistic product; the artwork is often the place where language fractures.

The paradox becomes evident. The more we try to “understand,” the further we drift from the very nature of the aesthetic experience. Understanding becomes a filter that neutralizes what is most alive in the work: its ability to produce friction within our thinking.

Roger, with his disillusioned sarcasm, expressed it more precisely than any theory could:

“It’s when you don’t understand that the work is doing something. If you feel comfortable, nothing is happening.”

He was right. Comfort is the terrain of repetition, predictability, pacified aesthetics. But contemporary art rarely operates there. It prefers unstable ground, the territory where understanding is not an achievement but an open question.

Misunderstanding, far from being a mistake, is often the most authentic form of reading. It is the moment when the work stops being an object and becomes an experience. And an experience cannot be “understood.” It can only be crossed.

The resistance to clarity, then, is not a communicative failure. It is the way art restores complexity to the world, preventing us from filing everything away too quickly. Clarity is reassuring, but it is almost never transformative. Unintelligibility opens a breach: a mental corridor, a perceptual gap through which we glimpse what we did not yet know we could see.

This is why the paradox of understanding is not something to be solved but something to inhabit.

Art does not ask us to understand. It asks us to remain.

In that suspended tension between what we see and what we do not yet know how to say.

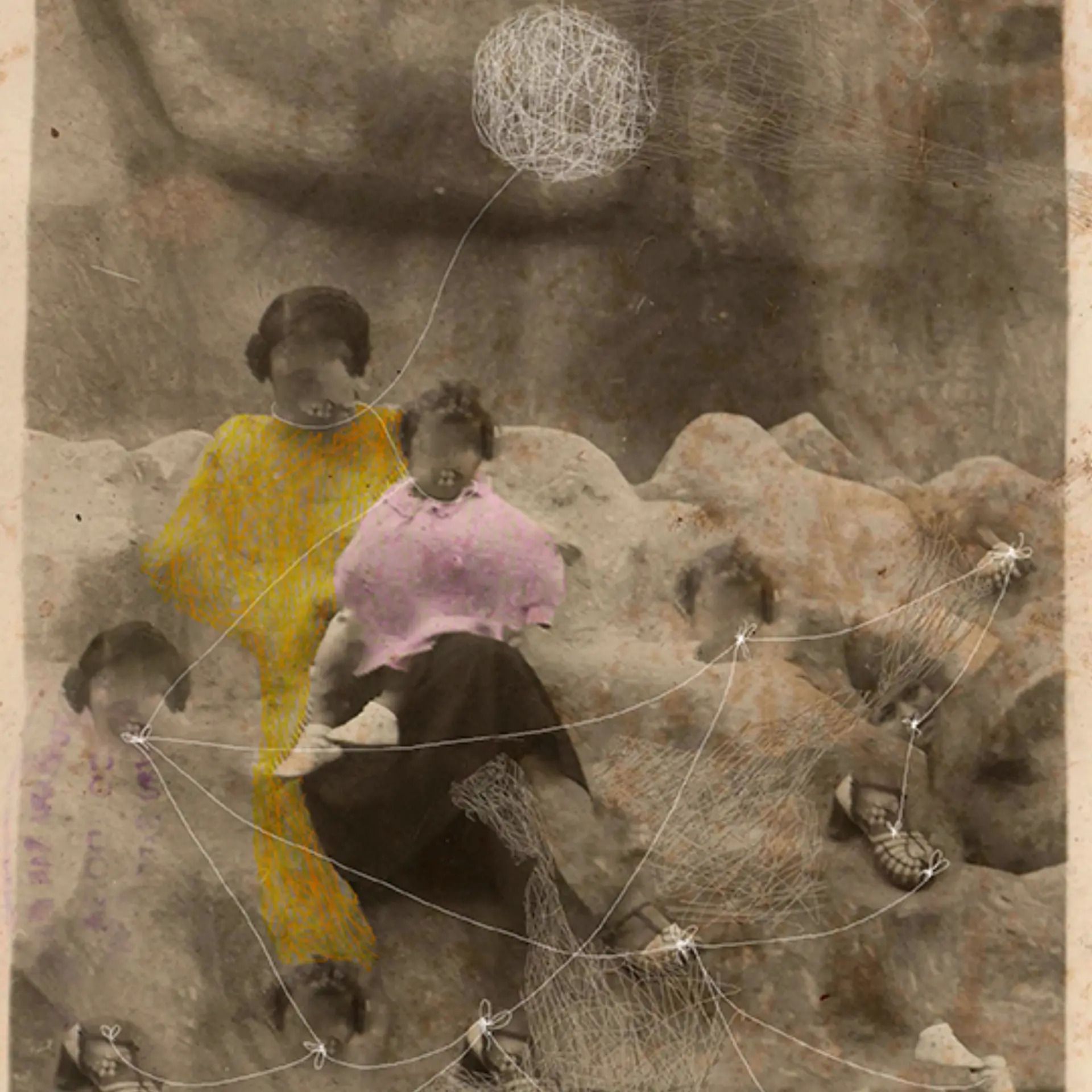

AI-generated image created by Fakewhale.

Lexicon and Abyss: How the Language of Art Creates Distance (and Desire)

Roger often said that the problem with contemporary art is never the work itself. It is the vocabulary that surrounds it. “The works speak. It’s everything around them that screams,” he would mutter, flicking his ash with the weary grace of someone who had witnessed far too many openings and too many catalogue essays written to be understood only by their authors.

The truth is that the lexicon of contemporary art operates like a semiotic barrier: not because it is inherently complex, but because it is built to define territories of belonging. Those who master the language of art move with ease; those who do not remain at the threshold, caught in a limbo of embarrassment and interpretive pleading. The issue is not understanding the work, but understanding how to speak about it.

Language becomes a device of power: a filter, a boundary. Each term, “hyper-contemporary,” “post-conceptual,” “site-specific,” “relational aesthetics”, functions like a passkey to a community that has legitimized itself through its own linguistic code. The lexicon, even before the artwork, determines who is allowed to join the conversation.

And yet this system is not only exclusionary; it is also seductive. Linguistic opacity generates desire. The more obscure a term is, the more it seems to guard a secret. Distance produces fascination; the semantic abyss becomes an attractor. Those who do not understand want to understand, and in that desire, they move closer to the work in ways that clarity could never permit.

It is an ancient mechanism: what escapes becomes something to pursue. What hides accrues value. Contemporary art, often unintentionally, feeds this dynamic. The word does not clarify; it evokes. It does not explain; it complicates. And in that complication, it opens an imaginative space that transparency inevitably suffocates.

Roger, with his sharp irony, distilled it perfectly:

“If you get it on the first try, it isn’t art. It’s communication.”

He wasn’t entirely wrong. The language of art is not meant to lock down meaning, but to keep it suspended.

The distance generated by the lexicon, that famous abyss so many fear , is not simply an obstacle. It is an integral part of the experience. It prevents the work from being immediately reduced to a single meaning, from being consumed too quickly. In an age obsessed with instant legibility, the cryptic language of art becomes a form of resistance.

Yet the contradiction must be acknowledged: this language, created to protect the complexity of the artwork, often ends up concealing it. Words that were meant to open pathways turn into walls. Discourse becomes autonomous, self-referential. Art stops being looked at and starts being discussed, as if the work were merely a pretext for theoretical debate.

And yet, despite everything, the lexicon of art retains a certain power. It enables us to articulate the ineffable, to give shape to what cannot be reduced to a simple concept. It is an imperfect language, but it is the only one we have for speaking about what refuses to be captured.

Its limit is also its strength: it generates distance, and in that distance, it ignites a desire to draw closer.

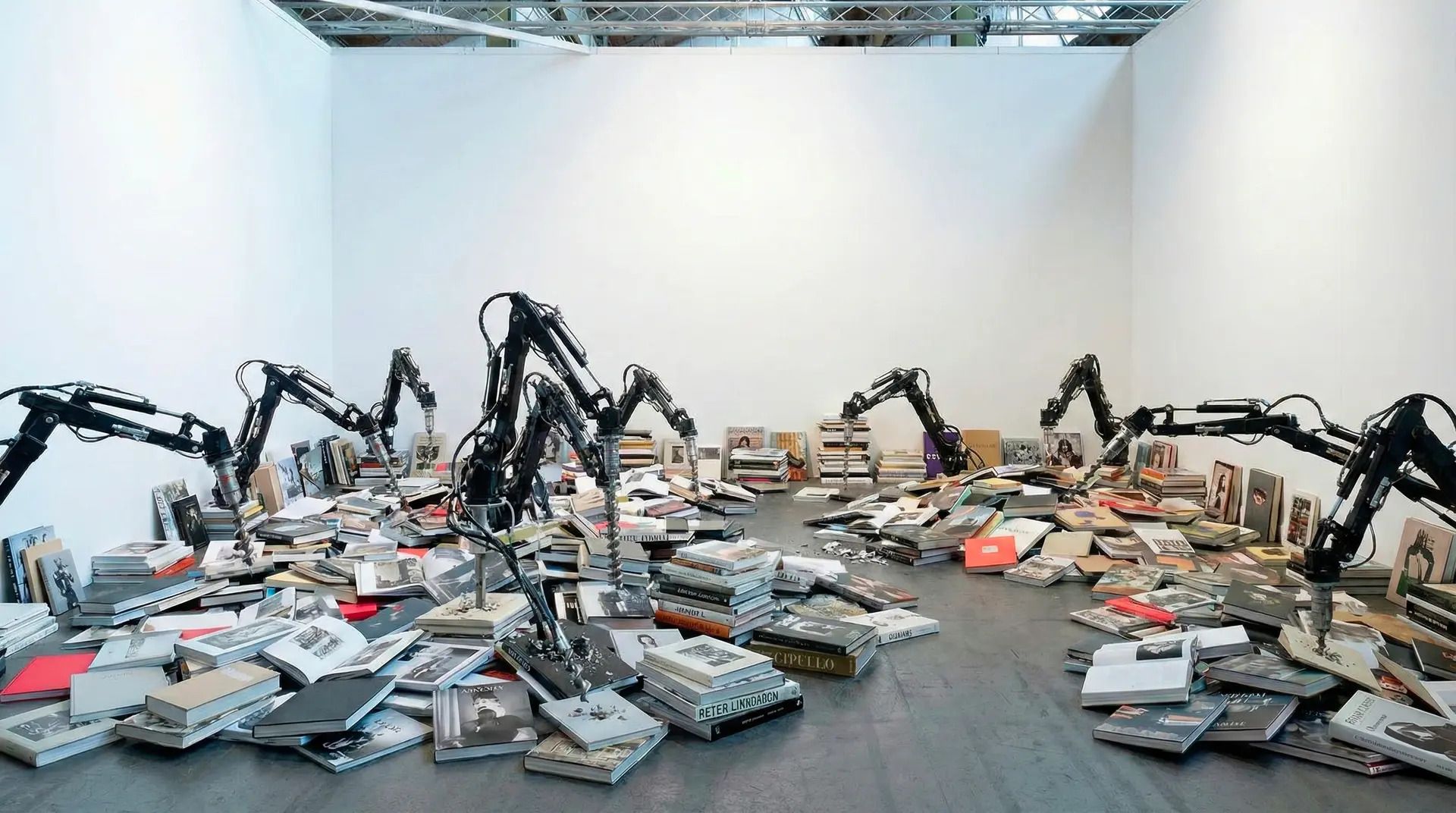

AI-generated image created by Fakewhale.

Reading as Relation: From Interpretation to Involvement

For Roger, reading a work never meant interpreting it. “Interpretation is what you do when you’re afraid to listen,” he would say, dryly, as he adjusted paintings no one fully understood, not even him, if we are being honest. And it is striking how that line, spoken with the air of someone who had no intention of theorizing, contains one of the most crucial distinctions in the experience of contemporary art: interpreting is not the same as being involved.

Interpretation is, in fact, an act of control.

It neutralizes the unease an artwork might generate, reducing it to a formula, a concept, a tidy explanation. It is the deeply human attempt to confine the work within a familiar order.

Involvement, by contrast, is a vulnerable gesture.

It asks us to accept openness, ambiguity, the possibility that the work may move us without offering a manual for how to receive it.

Reading a work, then, is not a cognitive activity but a relational one.

The real question is not what does it mean?, but what is it doing to me?

Not what is the artist trying to say?, but what happens when I place myself before this image, this object, this gesture?

From this angle, the artwork is never a code to decipher; it is an interlocutor.

It does not answer, it questions.

It does not clarify, it exposes.

It does not instruct, it introduces us to a form of otherness.

Involvement requires a kind of emotional and perceptual availability that interpretation often suppresses. To interpret, one must already know; to be involved, one must be willing to be surprised.

The former reassures; the latter transforms.

And the paradox is that when a work truly functions, it does not need to be understood. It makes itself understood only to the extent that it concerns us, interacts with our perceptual system, our inner archives, our expectations, or our vulnerabilities.

A work is never the same for two people, not because the multiplicity of interpretations is a democratic virtue of criticism, but because every relation is singular.

It is an encounter, not an equation.

Yet within the art system the pressure toward interpretation persists, as though it were the definitive measure of experience. Roger would shake his head:

“It’s like explaining a joke: it only works until you explain it.”

If reading is relation, it does not need to become theory. It can remain a contact, a vibration, a temporary drift in thought. It does not invite mastery, but presence.

In this sense, reading a work means relinquishing the impulse to put it in order, allowing instead for a more uncertain movement: a listening, a contact, a small internal misalignment.

True reading does not reduce, translate, or close. It receives.

It is there that the work begins to operate, not when we understand it, but when we make ourselves available to be touched by it.

AI-generated image created by Fakewhale.

AI-generated image created by Fakewhale.

The Value of Not Understanding: An Aesthetics of Uncertainty in the Contemporary Era

Old Roger had a theory of his own: he believed the most common mistake made by viewers, and often by artists themselves, was assuming that understanding was the natural endpoint of art. “Come on,” he would say. “If art were truly understandable, it wouldn’t be art anymore. It would be a public notice.”

And he said it without cynicism, with a kind of fierce tenderness, like someone defending a precious secret.

In the contemporary era, dominated by algorithms that anticipate our preferences and platforms that turn everything into instant consumption, art remains one of the last spaces where uncertainty is not a system error but a resource.

Not understanding becomes a gesture of resistance, an unexpected pause in the endless flow of prepackaged meanings.

The paradox is striking: we live in a world that demands absolute transparency, yet our cognitive vitality still depends on our ability to dwell in the opaque.

The mind grows when it encounters what it cannot immediately name.

Aesthetic uncertainty, then, is not a deficiency but a generative force.

It is the fissure through which thought can enter the work without colonizing it.

It is the moment in which the viewer interrupts their cognitive habits and leans slightly beyond the edge of what they already know.

Not understanding is, in this sense, an invitation:

an invitation to stay, to look longer, to dismantle the expectation of an immediate reading.

It is a deceleration that returns complexity to us, as if the work were saying, “Do not rush. Do not reduce me. Do not close me.”

And it is no coincidence that the works that stay with us are not the ones we have understood, but the ones that keep asking something of us.

Aesthetic memory does not retain answers; it retains questions.

Roger used to put it simply:

“A work you understand right away is a souvenir. A work you don’t understand is a companion.”

In an age when everything strives to be instantly explained, even emotions, even images, contemporary art can offer an opposite pedagogy: a pedagogy of uncertainty.

It reminds us that not everything meaningful must become clear, and not everything obscure is incomprehensible.

The value of not understanding lies precisely here:

in opening us to a world where complexity is not a problem to solve but a space to inhabit.

In revealing that an artwork does not offer us a truth, but a condition: the possibility of becoming different, more sensitive, more permeable after encountering it.